Across the world, people have always found ways to preserve their stories. From wampum belts in North America to kente cloth in West Africa, objects have carried memory and meaning for centuries. These practices stretch across continents and faiths—from Torah scrolls to the Christian cross. Today, these keepsakes still remind communities of who they are and how they came to be.

This story explores how people across cultures have transformed memory into something tangible, whether it be songs that map the land, carvings that embody spirit, or texts that carry divine words. Through these objects, we trace the human instinct to hold stories in our hands, to make meaning last beyond the voice that first told it.

But, to truly understand the meaning of these objects, we must first go back to where their stories began, back to when everything was spoken and nothing yet written.

Oral Traditions: The First Storytelling

Before writing, there were voices. Across continents, people once carried entire histories in memory—passed from one generation to the next through stories, songs, and spoken law. Oral tradition was humanity’s first archive, preserving identity, knowledge, and culture long before words were set down in ink.

In West Africa, griots—storytellers, historians, and musicians—kept the genealogies of kingdoms alive through rhythm and song. In ancient Greece, bards recited long epic poems like the Iliad and Odyssey entirely from memory, while Norse skalds performed sagas that recorded the deeds of ancestors.

Among the world’s most enduring oral traditions are those of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, whose storytelling systems remain deeply tied to the land. Their Songlines trace the journeys of ancestral beings, mapping waterholes, landmarks, and sacred sites.

“See the connectivity between all of the elements, between the sky, between the Earth, between the water, between magnificent sacred sites that are in the landscape that connect our people through this ancient wisdom and these ancient stories in song”

— Dr Anne Poelina, Nyikina Warrwaare

Woven through the land’s oldest stories is the Marlaloo Songline, telling of two serpents who journeyed across Country, naming sacred places and shaping the earth as they went. Passed down through generations, it connects people to Country through voice and rhythm, keeping both geography and identity alive through song.

Watch Elders as they sing and breathe life into the Marlaloo Songline:

Each Songline acts as both story and map, linking people to Country and to one another in a living network of memory and belonging.

As stories travelled farther from their tellers, people found new ways to keep them close. Across cultures, words were transformed into patterns, beads, and carvings.

Totem Poles: Carved Histories of the Pacific Northwest

First traced to the Haida peoples, totem poles have long stood along the Pacific Northwest Coast as carved testaments to memory. From Haida Gwaii to Haisla territory, these towering cedar sculptures carry histories in their form. They are stories of lineage, loss, and belonging told not through words, but through wood. Each figure carved into the grain becomes a chapter where ancestors, animals, and spirits entwine to teach lessons, honour alliances, and preserve the unseen.

One such story is carried in the G’psgolox Totem Pole raised in 1872 after an epidemic devastated a community. Its carvings record a vision experienced by a Haida chief who, guided by the spirit Tsooda, sought balance between life and death. At the top, Tsooda wears a revolving hat symbolizing wisdom and guidance. Below him sits Asoalget, a spirit messenger, and a mythical underwater grizzly, a being of power and transformation. Together, these figures tell a story of grief transformed into renewal, carrying a legacy meant to be seen, remembered, and passed down through generations.

For generations, poles like this one have stood as more than monuments. They are teachers, storytellers, and archives. Each one passes on values and history through its figures. To those who know how to read them, they speak of community, connection, and continuity. Even as cedar ages and colours fade, the stories remain, carried forward by each new generation who looks up and listens.

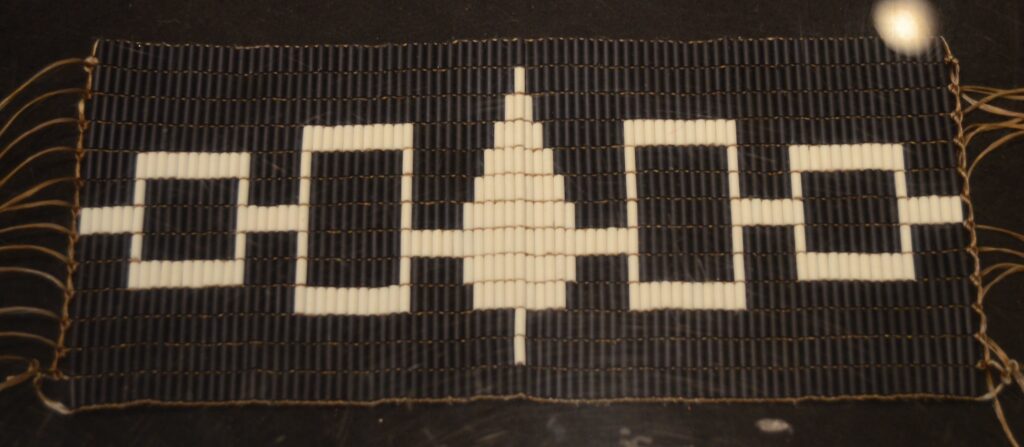

Wampum Belts: Shell Beads as Living Records

Like the cedar poles of the Northwest, other nations found ways to give their stories form. Along the Eastern Woodlands, memories were woven into wampum—beads crafted from purple and white clamshells— instead of carved. These beads, spun into intricate lines, were fashioned into “wampum belts,” acting as living records that bare the history of treaties and alliances, their designs preserving collective memory through patterns of shell.

“The speaker puts the words of the agreement into the wampum as the strings or belts are woven together.”

At the Onondaga Nation—one of the five founding nations of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy—the Keepers of the Central Fire continue to safeguard these sacred belts. For centuries, they have carried the stories of peace and governance that shaped Indigenous diplomacy long before the written word arrived.

Two belts remain famous today:

- The Penn Treaty Belt: It depicts two figures—one Lenape, one Englishman—clasping hands in a fragile promise of peace.

- The Hiawatha Belt: It records the confederacy’s founding. With its linked squares and central tree representing the Five Nations beneath the Tree of Peace.

Centuries later, these belts are still carried into council circles, not as relics behind glass, but as living storytellers reminding the Haudenosaunee of their past and their obligations to the future.

“It was like a historic document to us, a living document, and it told our story for generations.”

— Paula Peters, Mashpee Wampanoag historian and cultural leader

Kente Cloth: Weaving Proverbs into Pattern

In the former Asante Kingdom (modern-day Ghana), another form of woven storytelling emerged: kente cloth. According to the Minneapolis Institute of Art, kente originated as ceremonial wear for royalty in the 17th century. Each narrow strip of woven silk or cotton carried a name and meaning, often inspired by Akan proverbs or historical events.

“Kente is more than just a cloth. It is an iconic visual representation of the history, philosophy, ethics, oral literature, religious belief, social values, and political thought of West Africa.”

Colour symbolism gave the cloth its voice:

- Gold signified royalty and wealth.

- Green symbolized renewal and growth.

- Black expressed spiritual strength and maturity.

A weaver might create a new pattern to commemorate a chief’s coronation or a season of good harvest, making the cloth a “living record” of community milestones. Today, kente has expanded beyond royal courts to symbolize cultural pride across Ghana, West Africa, and the African diaspora, appearing in graduation stoles, ceremonies, and festivals worldwide.

Watch as a Ghanaian weaver brings stories to life through kente, each pattern and colour she weaves carrying a proverb, a memory, and a message:

Just as kente threads stories into fabric, many of the world’s great religions have woven meaning into their sacred symbols. Whether in wood, parchment, or gold, faith traditions found their own ways to make story visible and lasting.

Sacred Objects of Faith: Stories in Symbols

Across religions, these sacred forms carry not only history but devotion, becoming vessels of memory, faith, and law.

The Christian cross is perhaps the most familiar of these symbols. Once an instrument of execution, it became a sign of sacrifice and renewal. Whether carved in wood, cast in metal, or worn close to the heart, the cross tells the story of Christ’s suffering and resurrection. Standing as a reminder of endurance and grace that has travelled across centuries and continents.

The Torah scroll holds a similar reverence in Judaism. Each one is handwritten by a trained sofer (scribe) on parchment prepared from kosher animal hide. The process is painstaking and sacred, where even a single error can render a scroll unfit for ritual use. When read aloud in synagogue, its words are sung in ancient melodies, merging the oral and the written into one act of remembrance.

“The Torah is a tree of life to those who cling to it. All who uphold it are happy”

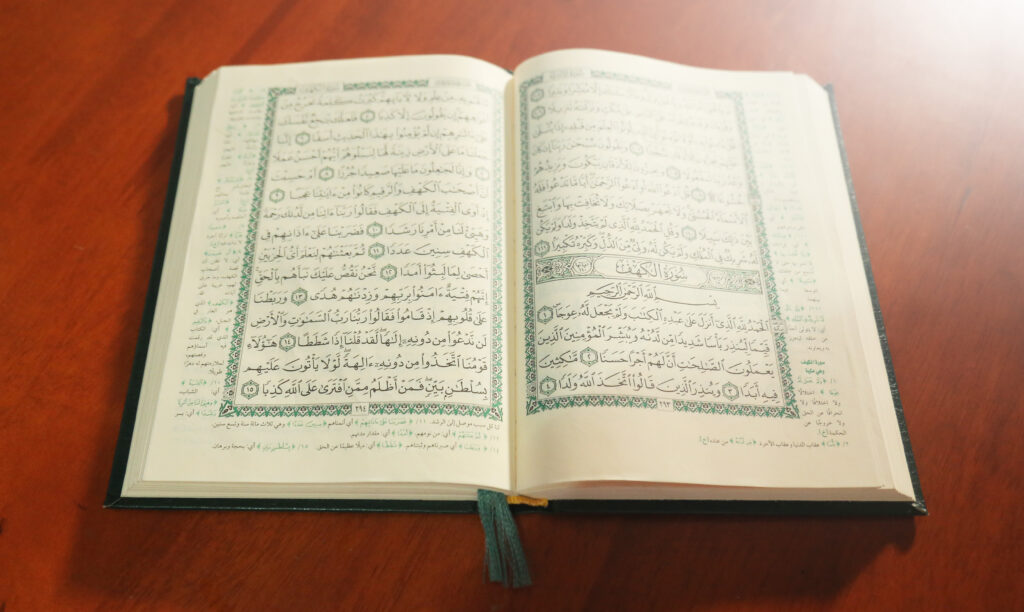

The Qur’an manuscript is equally revered. As The Met’s The Written Word in Islam explains, “Because of the exalted position of the Qur’an in Muslim societies, historically special attention was paid to the production, illumination, decoration, and display of Qur’an manuscripts.”

“Due to its association with the written word of God, calligraphy is considered by Muslims to be the highest art form.”

Luxuriously illuminated Qur’an manuscripts were often placed on carved wooden bookstands—rahla—and displayed in mosques and religious schools (madrasas). These manuscripts, adorned with gold leaf and intricate borders, transformed words into images of devotion. To see one open beneath lamplight was to witness faith turned visible.

Though these sacred objects reach back thousands of years, the impulse behind them remains unchanged. Each one tells a story of belief and beauty, of a people striving to give lasting form to the divine.

Across time and culture, the materials may change but the impulse remains the same. We make meaning tangible because stories are what keep us human. They remind us of who we are, and who we hope to be.

From the first oral traditions to today’s digital archives, each generation finds its own way to resist silence. Whether sung beneath open skies, woven in silk, or carved into stone, every culture leaves behind a trace — a keepsake of its voice.

These objects are the conversations that continue long after their makers are gone. And in listening to them, we remember that storytelling, in all its forms, is how we endure.

References

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (n.d.). Marlaloo Songline. https://aiatsis.gov.au/explore/marlaloo-songline

Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies. (n.d.). Songs Australia. https://aiatsis.gov.au/about/connect-us/make-difference/songs-australia

Biblical Archaeology Society. (2025, September 30). The staurogram. Bible History Daily. https://www.biblicalarchaeology.org/daily/biblical-topics/crucifixion/the-staurogram/

British Museum. (n.d.). Object H_1902-0315-13 (Collection object). https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/H_1902-0315-13

CBC Radio. (2020, September 18). 350 years of searching: Wampanoag still looking for historic wampum belt. CBC News. https://www.cbc.ca/radio/unreserved/mayflower-400-a-deep-dive-into-american-thanksgiving-1.5807974/350-years-of-searching-wampanoag-still-looking-for-historic-wampum-belt-1.5807976

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Griot. https://www.britannica.com/art/griot

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (n.d.). Skald. https://www.britannica.com/art/skald

Ganondagan State Historic Site & Seneca Art & Culture Center. (n.d.). Wampum. https://www.ganondagan.org/wampum

Haida Nation. (n.d.). Haida Nation. https://www.haidanation.ca/

Haudenosaunee Confederacy. (n.d.). Haudenosaunee Confederacy. https://www.haudenosauneeconfederacy.com/

Jewish Virtual Library. (n.d.). The Torah scroll. https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/the-torah-scroll

Minneapolis Institute of Art. (n.d.). Asante Kente cloth [Artwork in focus]. https://new.artsmia.org/programs/teachers-and-students/teaching-the-arts/artwork-in-focus/asante-kente-cloth

Onondaga Nation. (n.d.). Wampum. https://www.onondaganation.org/culture/wampum/

Panorama Journal. (n.d.). Re-reading wampum. https://journalpanorama.org/article/re-reading-wampum/

Peacock, S. (2024). Repatriation of the G’psgolox Totem Pole: A study of its context, process and outcome. International Journal of Cultural Property. https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/international-journal-of-cultural-property/article/repatriation-of-the-gpsgolox-totem-pole-a-study-of-its-context-process-and-outcome/C195CB8F432C4BF2ADD10C88E8792484

Sefaria. (n.d.). Proverbs 3:18 (Hebrew–English). https://www.sefaria.org/Proverbs.3.18?lang=he-en&utm_source=myjewishlearning.com&utm_medium=sefaria_linker

Smarthistory. (n.d.). Kente cloth. https://smarthistory.org/kente-cloth/

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). Calligraphy in Islamic art [Essay]. https://www.metmuseum.org/essays/calligraphy-in-islamic-art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art. (n.d.). The written word in Islam [Educator resource]. https://www.metmuseum.org/learn/educators/curriculum-resources/art-of-the-islamic-world/unit-one/the-written-word-in-islam

World History Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Greek literature. https://www.worldhistory.org/Greek_Literature/

World History Encyclopedia. (n.d.). Hiawatha belt (Image). https://www.worldhistory.org/image/13279/hiawatha-belt/